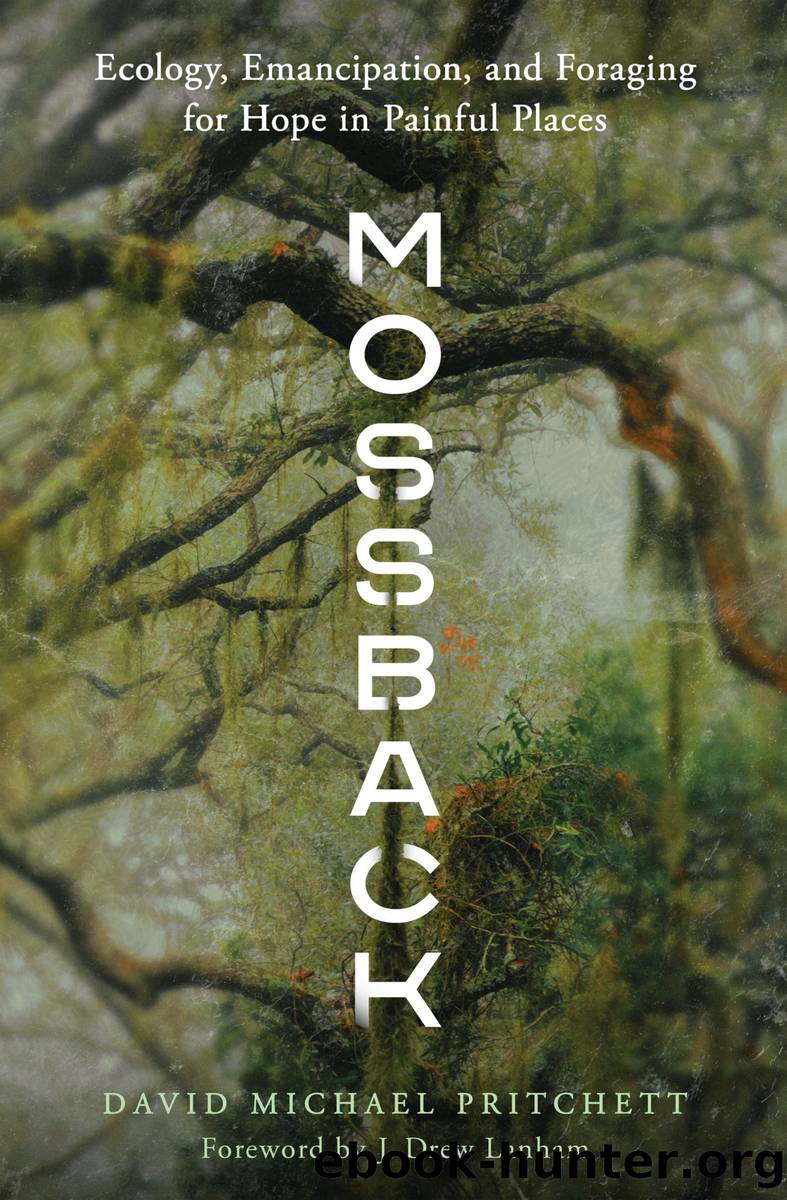

Mossback by David Michael Pritchett

Author:David Michael Pritchett

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Trinity University Press

One example of birds as messengers comes from a formerly enslaved person in the South. Louis, who escaped the plantation and lived in a den in the woods, explained how interspecies allyship helped him: âCanât nobody come along without de birds telling me. Dey pays no minâ to a horse or a dog but when dey spies a man dey speaks.â9

Over time, acts of deep listening can lead to human-bird communications and partnership. The legendary honeyguides of Africa respond to a whistled call from hunters and lead the hunter to a beehive full of honey. The hunter is then expected to share some of the bounty with the feathered guide. Inuit hunters of North America describe calling magic words to ravens, who then lead them to polar bear or caribou.10 In return the hunter leaves some choice meat for the ravens.

So when we listen to the song of birds, we expand our understanding in real time. Silence, alarm, or birdcalls tell us much about the forest or field we walk in. Through hearing, along with our other senses, we are mapping the world, creating a cosmology, one taste, one smell at a time. We learn through touch that the world does not end at the edge of our fingertips.

All perception is, in fact, a caress, a touch, of sorts. Sensory cells contain hairlike cilia involved in perceiving. Sound waves drum on fluid in your inner ear membrane, converting waves in the air to waves in the snail-shell spiral of your cochlea. Here the fluid waves bend the sensory hairs like kelp floating in an ocean wave, and these sensory cells, when bent, communicate sound to your central nervous system. In your eyes, rod cells have a cilia structure packed with photoreceptors that, when âtouchedâ by photons, send an electrical signal to your brain.11 Similarly, when molecules from the air dissolve into nasal mucus and contact the cilia of olfactory cells, a neural impulse of smell is sent to your brain. As with smell, food particles in the mouth engage proteins in the ciliary structures of your gustatory cells, allowing you to taste your food. Mechanical pressure bends hairlike projections from sensory cells, allowing your skin to feel. Our senses intimately engage us with the world. As writer Sophie Strand notes, âLife isnât composed of invisible ideal forms that hover beyond the realm of messy, generative embodiment. Life is haptic. Haptic is defined as âpertaining to and constituted by the sense of touch.â It is derived from the Greek word âhaptikosâ which means to come into contact and to fasten.â12 Molecules in our mouth press on the tongue. Light taps our retina. Odors touch our olfactory nerves. Sound waves brush our inner ear. Pressures on our skin stroke corpuscular cell fibers. We are constantly caressed, constantly fastened to the world around us, implicated in the ongoings of life.

We must perceive the world in order to act within it. All organisms chart their environment, a simple form of cognition, so that they can act within it according to their desires.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32538)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31936)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31925)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31912)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19032)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15927)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14477)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14046)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13873)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13341)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13333)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13229)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9313)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9271)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7487)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7303)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6741)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6610)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6261)